Apple Watch’s Wrist Position

Historically, watches have had very little information to offer, and essentially zero interaction. It used to be, after a watch was set to the correct time, there was no button pressing, scrolling, or reading to do*, only glances to see the time, each lasting a fraction of a second. With the introduction of Apple Watch this year, there will be a vast increase in the pressing, scrolling, and reading done on watches. To accomodate, people may chose to wear this device differently than their old watches: on the inside of their wrist. Let’s work through the anatomical reasons for this.

Back in November, Richard Burton strapped an iPhone to his wrist with a prototype of the Apple Watch’s face displayed on-screen. Doing so made it possible to examine the feel of interactions with the watch ahead of its release. When I say feel, I’m thinking specifically about the way the muscles and joints of our forearms feel as they work in concert to shift a watch face towards our gaze. After testing, Burton noted something interesting about wrist position:

As a result of the twisting strain, I wonder if this might lead to more people wearing [Apple Watch] on the inside of their wrist.

Let’s look at the bones, muscles, and tendons, the anatomy of this twisting strain.

First, some basics. You can wear a watch on two distinct positions on your wrist: the widespread top-of-wrist position and the far less common inside-of-wrist position. Let’s call top-of-wrist conventional and inside-of-wrist gauche†. When you check the time on a watch worn in the conventional (top-of-wrist) position, you elevate your elbow slightly and then pronate your hand, placing the watch face in a plane normal to your gaze. Conversely, when you wear a watch in the gauche (inside-of-wrist) position, you supinate your hand to bring the watch face into view.

Those links on pronation and supination are not particularly helpful for understanding my point. So, let’s do an exercise: place your entire forearm onto a flat surface (like a table) in front of you, palm down, with your fingers pointing straight ahead. Now, rotate your hand so your knuckles are touching the table and you can see your palm. The anatomical term for what you did when you rotated your hand is supination. You’ll feel some resistance to the rotation, just a little bit of strain in your forearm. If you repeat this palms-up/supination motion with your elbow closer to your side, you’ll notice your biceps (on the front of your upper arm) pulling to supinate your hand. Remember that point about your biceps.

Now, return your hand back to palm-down position. If you go past that postion, rotating your pinky skyward, like you were checking a watch in the conventional (top-of-wrist) position, you’ll notice a little more strain than before. So, if a device is positioned in the conventional or gauche position on your wrist, you’ll need to engage muscles, producing some strain in your forearm, in order to interact with it.

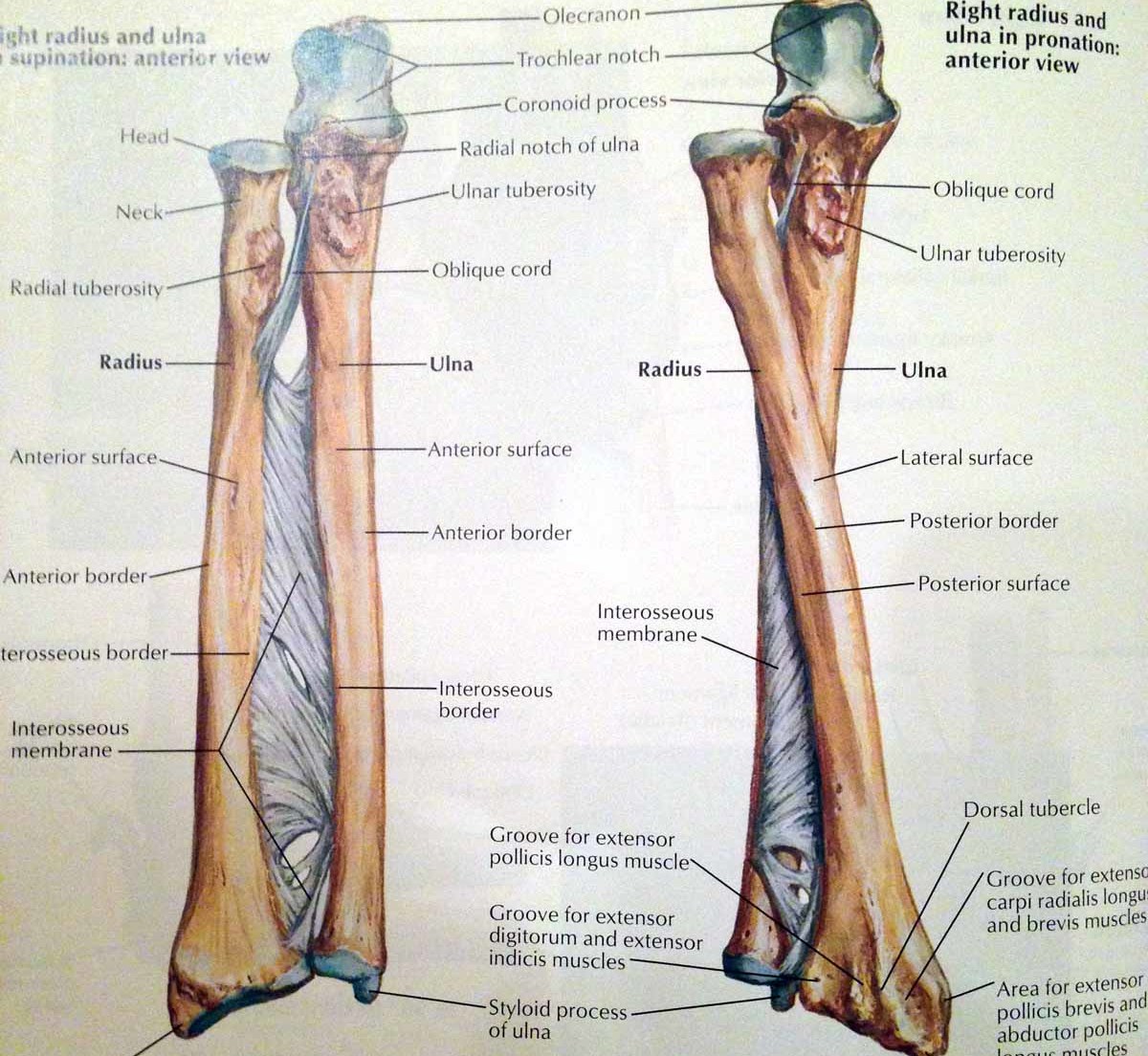

Why are you feeling strain? Explaining that requires an examination of your arm bones: the main bones of the forearm are the radius and ulna, and they slide around one another, not unlike the strands in a rope:

When you supinate your hand (left half of that image), the radius rolls across the ulna and the two become (essentially) parallel. Recall the effort this takes, your arm bones want to return to their original orientation‡. You can imagine this like you are untwisting the strands of the rope—it takes a certain amount of torsional energy to hold a rope in an untwisted position. When you return your palm to the table, the radius and ulna (rope strands) return to their overlapped, unstrained state. It also takes energy to twist rope strands together more tightly — analagous to pronation of the hand.

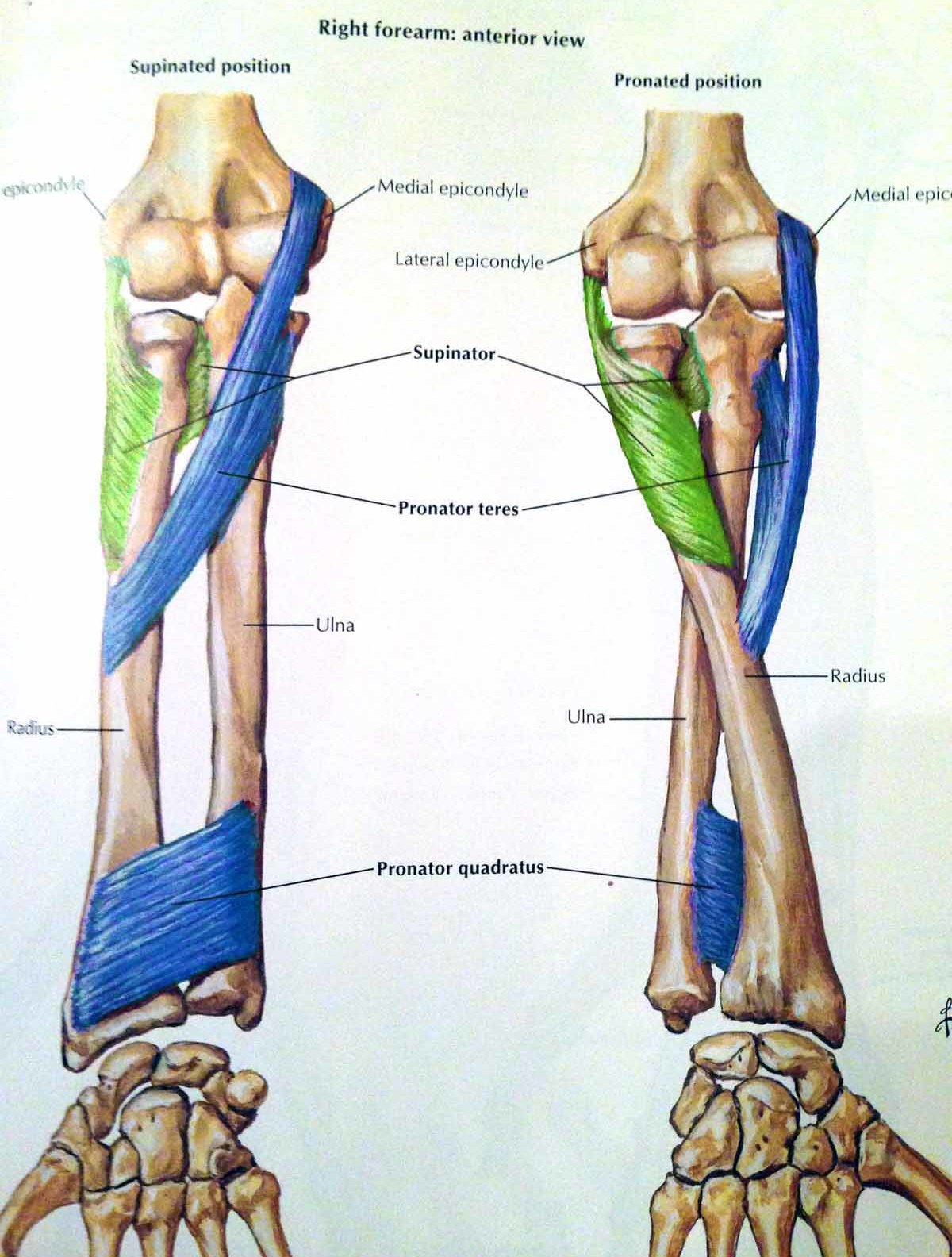

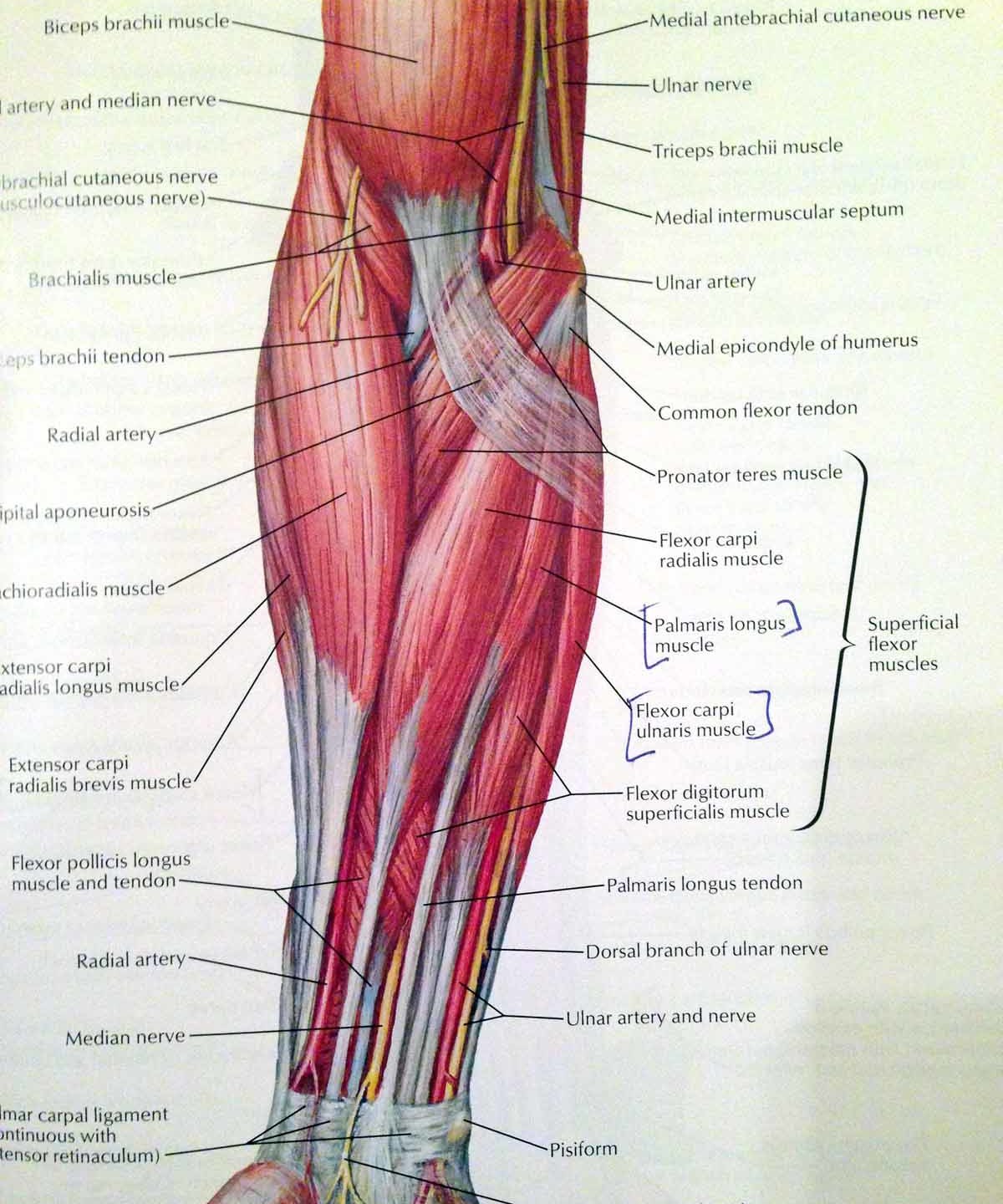

So if it takes effort to both supinate and pronate your hand, why would one be preferable? Answering this requires seeing some muscles on those bones. First, look at the pronator teres and pronator quadratus muscles below (highlighted in blue), the ones you use when when you pronate to view a watch in the conventional position. Next, look at the supinator (highlighted in green) and biceps bracii (top of second image) muscles, the ones you use when you supinate to view a watch in the gauche position.

Did you notice a difference between the muscles groups used for these opposing actions? The muscles that supinate are far more powerful compared to those that pronate (recall the strain in your biceps when you supinated your hand). This difference in size is mostly due to biceps bracii, which forms most of the front of your upper arm! Big muscles fatigue far more slowly than small ones, all else being equal. So, when you wear a watch in the gauche position, in defiance of convention and at risk of fashion faux pas, you recruit far larger, less fatigue-prone muscles during each interaction. This was of little importance when we used to quickly glance at our wrists, but in preparation for the pressing, scrolling, and reading we’ll be doing, we might consider flipping that watch display to the inside of our wrist.

* If you wound it, you did so when the watch was off your wrist. And yeah, yeah calculator watches.

† We get the word “gauche” from the French, where it means, literally, ‘left’ but the connotation when used in English is something unsophisticated or socially awkward. Something you can do, but in defiance of convention.

‡ Say “thanks” to your interosseous membrane.

Comments

John

I believe pronation for watch reading is more “ergonomically” correct. If the Apple Watch rests on the medial third of the internal aspect of the wrist, then maybe it would be ok. Your exercise in pronation/supination explains the movement well. But you can’t forget that our elbows are often at a 90 degree angle for any watch exercise. That changes angles considerably. Supination certainly is easier if your arm is pointed straight out, but full supination when your elbow is at a 90 degree angle is considerably more challenging than pronation. If the watch was placed in the center of the internal aspect of the wrist, I think long-term usage would be very uncomfortable. At least I would have a hard time keeping my arm in that position for a significant amount of time. But I don’t have muscles like Alex :)

Just my thoughts!

Alexander Micek

Hi John,

Thanks for the thoughtful response. What you are pointing out, that’s part of what I’m trying to figure out—what arm position will we interact with watch-like displays? If it tends to be with the watch-bearing wrist and hand in one’s lap or on a table, with elbow close by the side, gravity would help supinator and biceps bracii supinate that hand to view a watch in the gauche position, placing the entire system into a pretty neutral arrangement. Yet, fashion and tradition may still win the day and put the watch in the conventional position; think about how long it has taken for wallets to start to move to the front pocket. It will be interesting to watch.

Mykala

I’m going to go ahead and play super devil’s advocate, and suggest that neither pronation nor supination will ultimately be at play––because both seem like poor choices for long-term use. AND I still think the watch face will be placed inside the wrist! I know what you’re thinking… “What?! How could this be?” I shall explain: It seems the most comfortable position is one that mimics how we currently hold smartphones (pretend to pick up a phone and look at it), because it makes use of the larger muscles of the upper arm rather than requiring any awkward twisting in the forearm for long periods of time. Now, a watch face on the inside of the wrist, oriented vertically with its top at the bottom of the palm (so, turned 90 degrees from the traditional orientation), is the least demanding on small muscle groups and would allow the user to transition rather seamlessly from using a smartphone to using a watch.

What I think will really happen is that Apple will get a great deal of feedback regarding what is the optimal position and will eventually make the design more flexible, so the individual can adjust the orientation and positioning based on personal preference. Because some people will want to wear and use it just like a watch, and some people will want to use it like a smartphone… and that way everybody wins.

Alexander Micek

That is a really interesting possibility for the Apple Watch display orientation, Mykala. With the current hardware, the crown of the watch (when worn on the gauche/inside-of-wrist position) would be at an unintuitive orientation for its purpose (specifically, scrolling) if the display were rotated so the top was at the bottom of one’s wrist. However, this is something that could change in the future! You have me supinating my wrist and imagining a display on it! I wonder if this generation of Apple Watch is to get consumers comfortable with a watch-like device, and future ones will push the boundaries of what “watch-like” actually means, with ideas like your display rotation in play. After all, it was a couple of generations of iPod until we got the Shuffle.

John

We will have to see. I don’t know what functionality Apple is looking for in this watch or successors, and being an Android user I probably will not take the time to watch long videos about it (like I nerdily used to do).

If it is anything like the Samsung Galaxy Gear Watch, the primary function should be for quick and dirty phone access without whipping the 1/2 foot-sized smartphone from whatever pocket it barely fits into.

I for one can’t see people doing a lot of heavy work on a “watch phone” besides maybe text message reading or phone call operating when on the go. At least that is what I would do on it if I had one.

For more reading or web browsing, I would like to have a larger screen, but not too large as some of these screen sizes are getting kind of ridiculous….

Wallet in a front pocket? I would like really weird with my fat wallet in my front pocket, definitely not a fashion statement :)

John

Ha, a play on words (“time”), yay!

I did actually mean, “look weird,” not some weird fascination with the state of being weird.