Capital in the Twenty-First Century

I am reading the conclusions in Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century (It is rather unreasonable to try to wade through the 300 pages separating my progress in the book and the conclusions, given our two week old! So, I skipped to the end…). Here are some interesting quotes:

Social mobility:

Throughout most of the twentieth century, however, and still today, the available data suggest that social mobility has been and remains lower in the United States than in Europe. (p.484)

Education:

In other words, parents’ income has become an almost perfect predictor of university access. (p.485)

To be sure, university fees are much lower in Europe if one leaves Britain aside. In other countries, including Sweden and other Nordic countries, Germany, France, Italy, and Spain, tuition fees are relatively low (less than 500 euros). (p.485)

Stepping out of my quotation parade here—that means undergraduate educations are 12 times more expense on average in the United States than in Europe.

Social programs:

Finally, income support outlays (i.e. welfare) are even smaller (less than 1 percent of national income), almost insignificant when measured against total government spending.

…

Welfare benefits are questioned not only in Europe but also in the United States (where the unemployed black single mother is often singled out for criticism by opponents of the US “welfare state”). In both cases, the sums involved are in fact only a very small part of state social spending. (p.479)

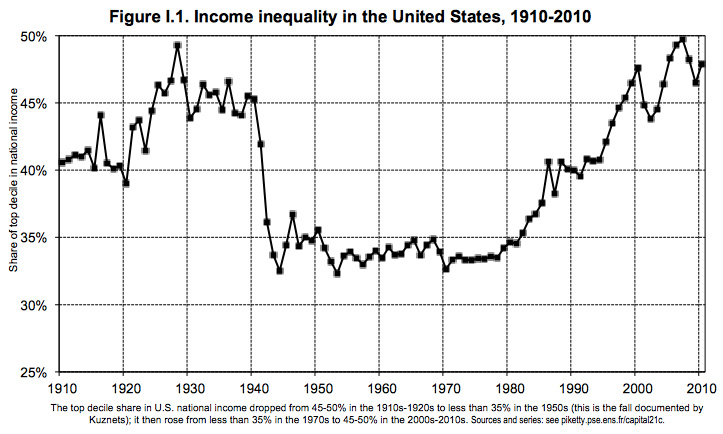

Income inequality:

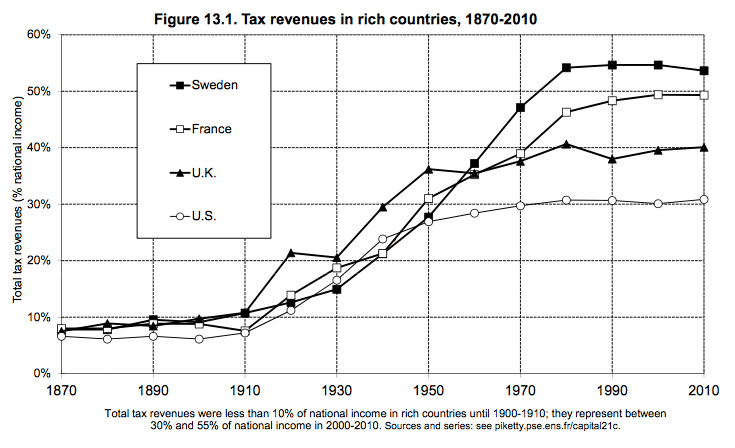

Tax revenues in rich countries:

Taxes:

[In the US] In 1942 the Victory Tax Act raised the top rate to 88 percent, and in 1944 it went up again to 94 percent, due to various surtaxes. The top rate then stabilized at around 90 percent until the mid-1960s, but then it fell to 70 percent in the early 1980s. All told, over the period from 1932-1980, nearly half a century, the top federal income tax rate in the United States averaged 81 percent.

It is important to note that no continental European country has ever imposed such high rates (except in exceptional circumstances, for a few years at most, and never for as long as half a century).

Particularly fascinating is that it is not theoretical that government created the middle class in the United States after World War II (see the income inequality chart above):

Concretely, the two phenomena are perfectly correlated: the countries with the largest decreases in their top tax rates are also the countries where the top earners’ share of national income has increased the most (especially when it comes to the remuneration of executives of large firms). (p.509)

As Piketty points out, the above is not explained by the theory of marginal productivity:

A more realistic explanation is that lower top income tax rates, especially in the United States and Britain, where top rates fell dramatically, totally transformed the way executive salaries are determined. (p.509)

And lets throw out trickle down theory while we are at it:

… there is no statistically significant relationship between the decrease in top marginal tax rates and the rate of productivity growth in the developed countries since 1980. (p.510)

Loving this:

According to our estimates, the optimal top tax rate in the developed countries is probably above 80 percent.

…

The evidence suggests that a rate on the order of 80 percent on incomes over $500,000 or $1 million a year not only would not reduce the growth of the US economy but would in fact distribute the fruits of growth more widely while imposing reasonable limits on economically useless (or even harmful) behavior.

…

A rate of 80 percent applied to incomes above $500,000 or $1 million a year would not bring the government much in the way of revenue, because it would quickly fulfill its objective: to drastically reduce remuneration at this level but without reducing the productivity of the US economy, so that pay would rise at lower levels. In order for the government to obtain the revenues it sorely need to develop the meager US social state and invest more in health and education (while reducing the federal deficit), taxes would also have to be raised on incomes lower in the distribution (for example, by imposing rates of 50 or 60 percent on incomes above $200,000). Such a social and fiscal policy is well within reach of the United States. (p.513)

But Piketty’s definitive solution is not based on marginal tax rates but rather on a “global tax on capital.” He spends the book explaining, illustrating, and providing evidence to show that r > g where r is return on capital and g is growth of income and output. That is “Once constituted, capital reproduces itself faster than output increases. The past devours the future.” (p.571).

Not “a” solution but the solution:

The right solution is a progressive annual tax on capital. This will make it possible to avoid an endless inegalitarian spiral while preserving competition and incentives for new instances of primitive accumulation. For example, I earlier discussed the possibility of a capital tax schedule with rates of 0.1 of 0.5 percent on fortunes under 1 million euros, 1 percent on fortunes between 1 and 4 million euros, 2 percent between 5 and 10 million euros, and as high as 5 or 10 percent for fortunes of several hundred million or several billion euros. This would contain the unlimited growth of global inequality of wealth, which is currently increasing at a rate that cannot be sustained in the long run and that ought to worry even the most fervent champions of the self-regulated market. (p.572)

Extraordinarily illuminating. I look forward to revisiting it in the future, when I’ve more time to ponder details and better understand what Piketty is saying.