Chalkin

When we draw with chalk on the driveway, Ess doesn’t call it “drawing” or “coloring” — her preferred term is “chalkin’”.

“We’re chalkin’, Mama!”

When we draw with chalk on the driveway, Ess doesn’t call it “drawing” or “coloring” — her preferred term is “chalkin’”.

“We’re chalkin’, Mama!”

Andrew Sullivan’s short and potent The Madness of King Donald levels-up when it ends with a subject rather more profound than our current administration:

I’ve managed to see Scorsese’s Silence twice in the last couple of weeks. It literally silenced me. It’s a surpassingly beautiful movie — but its genius lies in the complexity of its understanding of what faith really is. For some secular liberals, faith is some kind of easy, simple abdication of reason — a liberation from reality. For Scorsese, it’s a riddle wrapped in a mystery, and often inseparable from crippling, perpetual doubt. You see this in the main protagonist’s evolution: from a certain, absolutist arrogance to a long sacrifice of pride toward a deeper spiritual truth. Faith is a result, in the end, of living, of seeing your previous certainties crumble and be rebuilt, shakily, on new grounds. God is almost always silent, hidden, and sometimes most painfully so in the face of hideous injustice or suffering. A life of faith is therefore not real unless it is riddled with despair.

How efficiently he gets from his summary of secular liberals’ imperfect understanding to the realities of a life of faith. As a secular liberal guilty of precisely that imperfect understanding, reading this helped me understand that faith doesn’t resolve all existential angst or salve all philosophical bramble.

Jess Zimmerman illuminates more problems in our deeply sexist society with her “Where’s My Cut?”: On Unpaid Emotional Labor:

The originators and adherents of #GiveYourMoneyToWomen didn’t just suggest that women should get paid for existing, although yeah that too if you’re buying. Rather, women should get paid for all the work they typically do for free – all the affirmation, forbearance, consultation, pacifying, guidance, tutorial, and weathering abuse that we spend energy on every single day. Imagine a menu of emotional labor: Acknowledge your thirsty posturing, $50. Pretend to find you fascinating, $100. Soothe your ego so you don’t get angry, $150. Smile hollowly while you make a worse version of their joke, $200. Explain 101-level feminism to you like you’re five years old, $300. Listen to your rant about “bitches,” $infinity.

It was beautiful to watch #GiveYourMoneyToWomen unfold. Men got angry, and then women explained to them that to have their anger acknowledged, they would have to pay. This made them angrier, of course, but without a donation, who was listening?

Following EverydaySexism has helped me begin to see the grinding, humiliating, oppressive, equality-crushing mill of our society; one that produces suffering women endure knowingly and unknowingly. Reading pieces like Zimmerman’s are my next step in jumping from seeing to understanding. That way lies empathy.

Here’s a nice excerpt from Walking, by Henry David Thoreau:

My desire for knowledge is intermittent, but my desire to bathe my head in atmospheres unknown to my feet is perennial and constant. The highest that we can attain to is not Knowledge, but Sympathy with Intelligence. I do not know that this higher knowledge amounts to anything more definite than a novel and grand surprise on a sudden revelation of the insufficiency of all that we called Knowledge before—a discovery that there are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamed of in our philosophy. It is the lighting up of the mist by the sun. Man cannot KNOW in any higher sense than this, any more than he can look serenely and with impunity in the face of the sun: “You will not perceive that, as perceiving a particular thing,” say the Chaldean Oracles.

At first reading, it may seem to be an argument against Knowing anything but Thoreau declares “insufficiency” of knowledge in the philosophical, not the scientific sense. So, I feel that I can staunchly defend the merits of Science and Knowledge with a video like Science in America from Neil deGrasse Tyson, while nodding along with Thoreau about the importance of imaginatively underestimating how little we understand. That is to say: science is splendidly suited to uncovering truths (statistical significance), completing tasks (move this to there), advancing understanding (how are life and matter shaped), and setting the course of humanity (how should we behave to make sure our descendants don’t die). But if our hubris makes us believe the narrowness of our experimentation accounts for the broadness of the unknown, then we’re just punching buttons on a treadmill. For it is always the imaginative leap of the hypothetical that takes theory, instrumentation, experimentation from one plateau to the next.

Then I would say: science not governed by imagination, but alloyed with it.

“Ess, what do you want to do today?”

“I’m eat bear cereal all day long.”

It turns out that if you play the 1999 hit song “Say My Name” by Destiny’s Child to Ess while driving in the car, she’ll listen to it, and then ask you to play “Fooba Nane” again please. Then she’ll listen to it a few times in a row, and when the chorus says “Say ‘baby I love you’” she’ll go “no I LOVE YOU, Mama!” and it’ll become part of driving.

But then, in the dark, when Ess is falling asleep in her crib, just before Mykala is going to close the door for the night, Ess will ask her to “sing Fooba Nane.” And Mykala will oblige. And then, over the months, it will become a staple of Essie’s bedtime routine.

Mykala will be asked to change the lyrics to incorporate penguins brushing their teeth (with mama-dada toothpaste), exceptionally high-pitched bird chirping sounds, turtles, dogs, and cats — all singing their own lyrics to the original tune.

And that brings us to today. I look forward to hearing Mykala’s songs each night. I hope this phase lasts for a while.

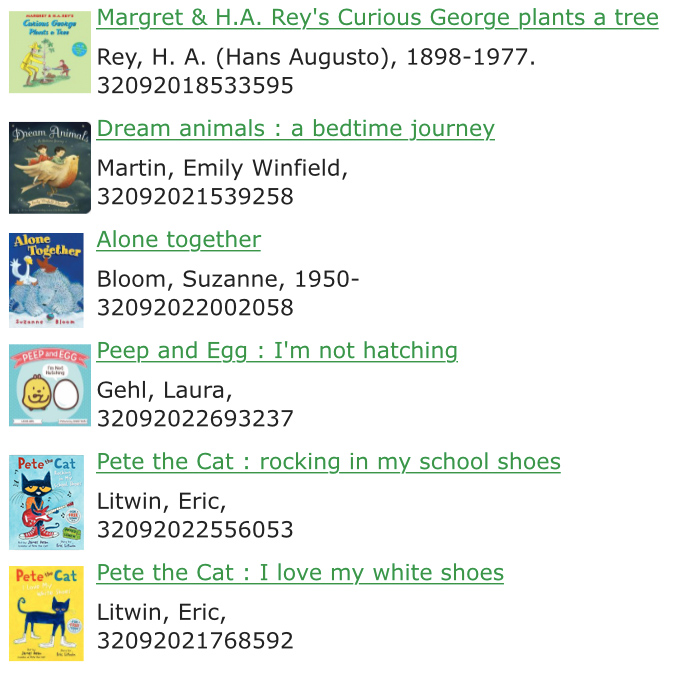

I thought it might be fun to occasionally write down which library books we’ve checked out and are reading to Ess. This is the current stack on our nightstand:

Ess went through a big “Pete the Cat” phase; now that she has those two books just about memorized, she is moving on to other things. (That’s good, because we have to return these books to the library soon.) There’s a call and response in those two Pete the Cat books:

“Does Pete worry?”

“Goodness, no!”

And as long as she’s not distracted putting a stuffed animal to sleep, or wrapping one monkey’s arms around another so they can be hugged all night, Ess will pipe up: “Goodness, no!”

I think Dream Animals by Emily Winfield Martin might be the most beautifully illustrated book we have yet seen.

It’s easy to breeze through the times when Ess is happy, to let her play on her own when she’s content. There are always adult things to be done: cleaning, bill-paying, paperwork, planning, reading pieces on politics, philosophy, coding… and I have noticed I tend to conflate the important tasks with the urgent tasks. I can usually complete the urgent ones while Ess plays, but with that momentum I find I am sailing into important things and then… not very important things.

There’s a speed bump before the fork in the road, but if I can maneuver to the alternate route, I end up in a mindset where I’m thinking about trying to participate with Ess. It isn’t obvious in the moment, but stepping back I realize the bill-paying and cleaning will be there long after Ess grows up. So the three of us have played Zingo (though at this age it devolves into Ess doing “let’s pitch all the pieces around”) and we read of course, but I’ve recently found something worth practicing. I was helping to get Ess out of the car the other day, and instead of thinking about getting her inside, so she could have a bath and get ready for bed, I tried to short-circuit my adult tasklist. I just stopped. And I looked at what Ess was doing. I mean, we are always looking at what Ess is doing (and Mykala is frequently cleaning up after what Ess was doing during the long days while I am at work), but this time I really tried to see.

Perhaps sensing this, Ess immediately began chattering away, narrating what she was imagining, what the two little play bugs she had were doing, going in and out of their house, where were they cold, where were they warm, can I hold this one, see how this one is clean and this one is dirty, and look how the antennae on this one are gone. (I’ve added a picture of what they look like when they’re new.)

Essie’s imagination, the world she’s in, has a richness that surpasses my own. Almost everything is new, and everything is interesting. Her excitement is contagious, her narration frequently hilarious, and her desire to share it all is easy for me, stumbling through the smokescreens of adulthood, to miss.

At the library, Ess found a toy stethoscope. Listening to its heartbeat sounds, she asked me what it was called and I told her.

Later on she declared that she’s going to have to use the check-up-scope to make sure her stuffed penguin was OK.

Check-up-scope.

“PEANUT!” Ess exclaimed ecstatically from the back seat of the car.

Our confusion gave way to realization: Ess had chewed through to the middle her of apple and saw its seeds.

Some things we eat, some things we don’t.

↓ More